Is Water Boiling Point always at 100°C

Is Water Boiling Point always at 100°C

The temperature often associated with boiling water is 100°C, but does water always boils at 100°C?

Boiling doesn’t always necessarily boils at 100°C!

Let’s take, for example, you have decided to have a meal on the beach, and you are going to prepare hard-boiled eggs. So you get your saucepan and your stove to boil water.

You light the stove, and away you go. All you have to do is wait. When the water starts to boil, place the eggs in the saucepan. Ten minutes later, the eggs are ready, and you tum the stove off. You have perfectly cooked the eggs, just the way you like them.

A few days later, your journey takes you into the mountain. Eager to exercise your expertise in boiling eggs, you get out the saucepan, stove, and lighter.

When the water starts to boil, place the eggs in the pan. Ten minutes later, you turn off the stove. Logically the eggs should now be ready the way you like them.

When you try the eggs again, you discover that the yellows are soft, although you’ve left them in the boiling water for 10 minutes, exactly as you had done on the beach!

How do you explain this? Do you have any ideas about how it happened?

The problem you’ve encountered with the eggs is due to e pressure effect!

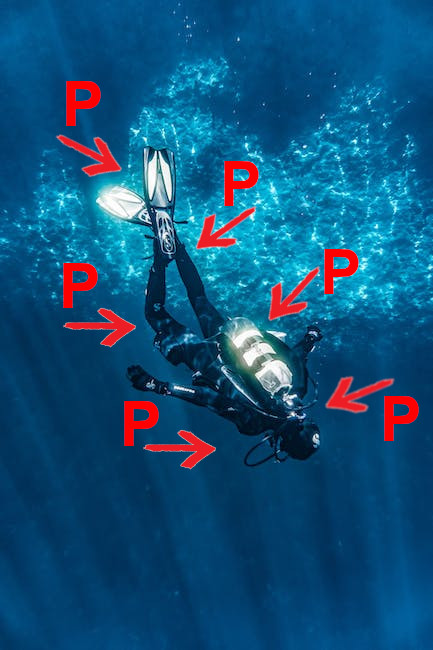

If you have ever done scuba diving, you will be familiar with pressure problems.

What happens is that the deeper a diver descends, the greater the pressure P that the water exerts on him becomes. For example, at a depth of 50 metres, the pressure exerted by the water is more than 5 bar (that is, five times atmospheric pressure).

This pressure is the result of the column of water above the diver. It is why the pressure increases with depth.

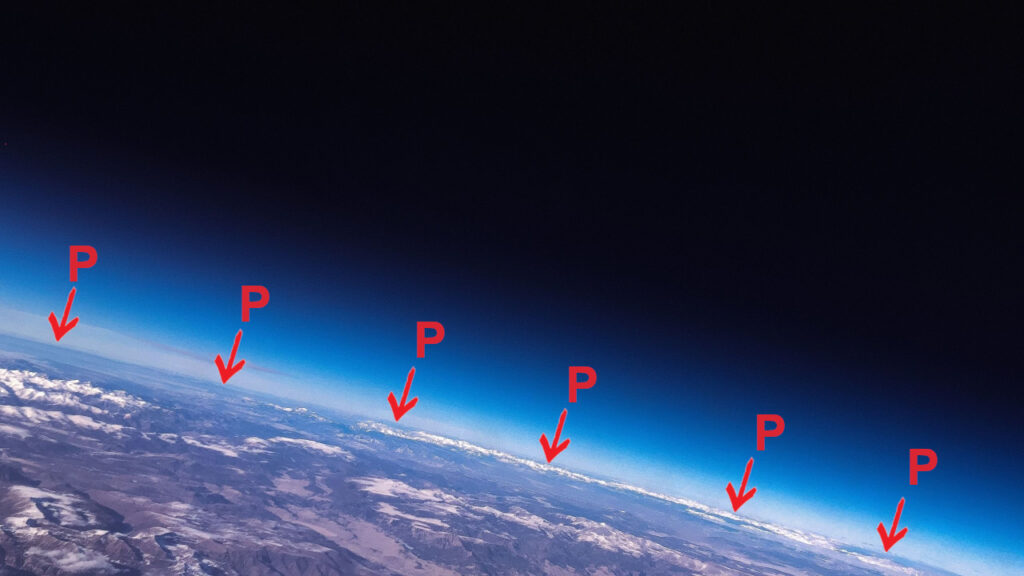

In the same way, there is a layer of gas around the earth known as the atmosphere. Its thickness can vary, but it is roughly about 20 km thick.

Like the depth of water exerts pressure on the diver, the depth of the atmosphere exerts pressure on the earth’s surface.

As you may know, this pressure is what we call atmospheric pressure.

At sea level, the atmospheric pressure is because of the depth of gas of about 20 km. But when we are at an altitude of 3000 m (i.e. 3 km), the depth of the atmosphere is only 20 – 3 = 17 km.

Therefore, the atmospheric pressure at 3000m altitude results from 17 km above air instead of 20 km at sea level.

It’s easy to understand why the atmospheric pressure gradually falls as we go to higher altitudes.

For your information, the agreed unit of pressure is the Pascal (Pa).

However, the bar or kilopascal (Bar or kPa) is typical in refrigeration. A Bar is essentially the atmospheric pressure that we measure at sea level, that is, at an altitude of 0 metres (we often say that 1 bar = 1 atmosphere = 101.3 kPa)

So, the higher you reach altitude, the lower the atmospheric pressure. For example, atmospheric pressure is 1.013 bar at sea level, but it’s only 0.7 bar at 3,000 metres and 0.4 bar at 7,000 metres.

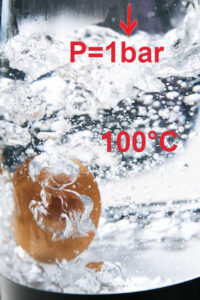

Let’s return to the boiling of eggs. At sea level, at an altitude of 0 metres, atmospheric pressure is 1.013 bar, and water normally boils at 100°C. At this temperature, eggs that have been in boiling water for ten minutes are perfectly hard-boiled.

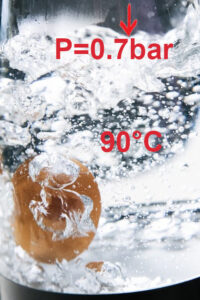

At an altitude of 3,000 metres, the atmosphere’s thickness is less, and atmospheric pressure is only 0.7 bar.

When it starts boiling, water has a temperature of only 90°C (instead of the 100°C above).

Let’s see if we can understand it better by exaggerating a little: if the eggs were left in the water for 10 minutes at 20°C, they wouldn’t cook at all!

The colder the water is, the more slowly the eggs cook. They perfectly cook if we immerse them for ten minutes in water at 100°C. If the water is only at 90°C, it’s logical to conclude that the eggs will be less well-boiled.

Note that at a 7,000-metre altitude, the thickness of the atmosphere is even less, atmospheric pressure is also smaller (it’s no more than 0.4 bar), and water boils at an even lower temperature: 75°C.

Of course, if we leave eggs in water at only 75°C for ten minutes, they won’t cook them.

We conclude that to hard-boil an egg, we must supply it with enough energy. The greater the altitude, the lower the boiling point of water, hence the more time it takes to cook the eggs. It is to supply them with enough heat to boil.

In other words, the lower the atmospheric pressure, the lower the boiling temperature of the water. See What is Boiling for an explanation of this effect.

These effects where the boiling temperature varies with pressure are significant if we want a good understanding of refrigeration systems!

Back to Basic!

Related

Read more: Fan wall

Read more: How to verify the percentage of outside air in an enclosure

Read more: BCA Part J5 Air-conditioning system control

Read more: Microbial Induced Corrosion (MIC) in Pipes

Read more: Is your kitchen exhaust system a fire hazard

Read more: What is coanda effect