What Happens in the Cold Heat Exchanger?

What Happens in the Cold Heat Exchanger?

Remember that R22 refrigerant vaporises at -42°C at atmospheric pressure by absorbing heat. R22 is, therefore, capable of absorbing heat from any material whose temperature is greater than -42°C. It is terrific, as it just so happens that we want to chill foods in our fridge whose temperature is higher than this.

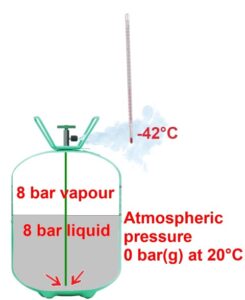

If the pressure in the cylinder that contains R22 is greater than atmospheric, when we open the valve, R22 emerges in a liquid state after passing through the dip tube.

At the valve outlet, we can see that the molecules of liquid at 8 bar expose to a much lower external pressure with a value of 0 bar gauge (that is, atmospheric pressure).

Since this external pressure is low compared to the internal pressure of 8 bar exerted by the liquid, the molecules of R22 liquid escape from each other and immediately evaporate, taking the heat required from the surrounding air.

It is why the thermometer placed at the cylinder outlet shows -42°C; the cooling of the surrounding air from +20°C to -42°C is simply due to the evaporation of R22. We know that the cooling capacity (that is, the capacity to absorb heat) depends on the flow of liquid R22.

To obtain a better thermal exchange, we could improve the system by passing the liquid through a heat exchanger, as we have shown.

By partially opening the cylinder valve, we can regulate refrigerant flow through the freezer. As the freezer’s outlet is open to the air, the pressure in this cold heat exchanger effectively equals atmospheric pressure. The R22 travels from the cylinder to outside air through the freezer.

So all we need to do is buy a cylinder of liquid R22, connect it to our cold heat exchanger, make it leak from the outlet of our freezer, and away we go!

As R22 evaporates at -42°C at atmospheric pressure, the freezer is cooled to a temperature close to -42°C. At this point, we could perhaps imagine an arrangement designed to chill the feed in our refrigerator, which is a bit more sophisticated than this.

We can construct our first refrigerator—the R22 cylinder placed at the rear of the fridge. A tube connects the cylinder to the cold heat exchanger, whose outlet is open to the atmosphere.

As the R22 is vaporising at -42°C at atmospheric pressure, the freezer temperature becomes low enough to make ice cubes and to chill the food stored in the fridge.

In the cold heat exchanger, the refrigerant absorbs heat and evaporates. It is known to refrigeration professionals as an evaporator.

Our refrigerator is interesting in principle. However, it possesses two huge inconveniences: Can you see what they are?

In reality, a refrigerator operating in this way possesses two major inconveniences;

First, we constantly lose refrigerant to the atmosphere. The R22 cylinder will rapidly become empty and need replacing frequently. It could be more practical, especially since R22 is so expensive.

Second, by releasing the R22 into the atmosphere, we are causing pollution, damaging the ozone layer. This layer protects the earth from the sun’s ultraviolet rays. R22 also adds to the greenhouse effect, causing a worrying global temperature increase.

So such a system is hardly acceptable; would you buy a highly polluting refrigerator that needs a top-up with expensive refrigerant daily?

Wouldn’t it be possible to recover the gaseous R22 at the evaporator outlet rather than stupidly release it into the atmosphere?

Back to Basic!

Related

Read more: Fan wall

Read more: How to verify the percentage of outside air in an enclosure

Read more: BCA Part J5 Air-conditioning system control

Read more: Microbial Induced Corrosion (MIC) in Pipes

Read more: Is your kitchen exhaust system a fire hazard

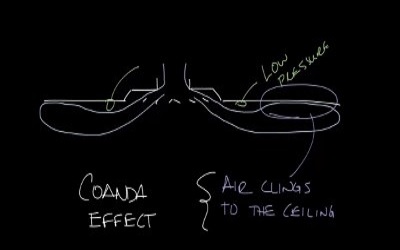

Read more: What is coanda effect